Blog News about Japan 未分類

Manekineko: Lucky Charm in Japan

<Beckoning Cats at Gotokuji>

When Ii Naotaka, a nobleman of the Edo era (1603-1868) was returning from a falcon hunting expedition, he saw a beckoning cat at the gate of the Gotokuji temple (now in Tokyo’s Setagaya City), and stopped in for a rest. Just then, a huge thunderstorm began, and Ii, who was happy to have found shelter from the rain, is said to have made a generous donation to the temple. From this legend, the temple became associated with the beckoning cat. Actually, however, it was the Imado Shrine in Tokyo’s Taito Ward that seems to have begun selling cats as iconic figures. When the cat’s right paw is raised, it beckons money; if its left paw is raised, it is summoning people.

Blog News about Japan 未分類

Japanese soy sauce factory

With its iconic bottle featuring a red capped dispenser, Kikkoman is synonymous worldwide as the image of Japanese soy sauce. Indeed, with its roots as manufacturer of soy sauce from 1661, Kikkoman is just as renown within Japan and has been the purveyor of soy sauce for the Imperial Family for over 100 years. Their factory in Noda city in Chiba Prefecture holds six tours daily where visitors can learn more about the process of making this famous fermented condiment.

Noda has historically been a town famous for making soy sauce. The reason is because of its ideal location. Situation at the junction of the Tone and Edo rivers, Noda had easy access to good quality soy beans, wheat and salt as well as a reliable water route transport to the markets in the capital of Edo, present-day Tokyo.

The Kikkoman soy sauce factory tour lasts approximately one hour and begins with a short video of how soy sauce is produced. It is a video worth watching carefully because it shows close-ups of how the process works. The tour itself does not give access to many of the rooms where production occurs. This is inevitable because fermentation is a process that requires facilities to be sealed off to control temperature and humidity. The tour itself consists of walking through the facilities and looking at a variety of panels depicting the process. Real samples of the various stages of soy bean fermenting are on display to look at and also to smell as well.

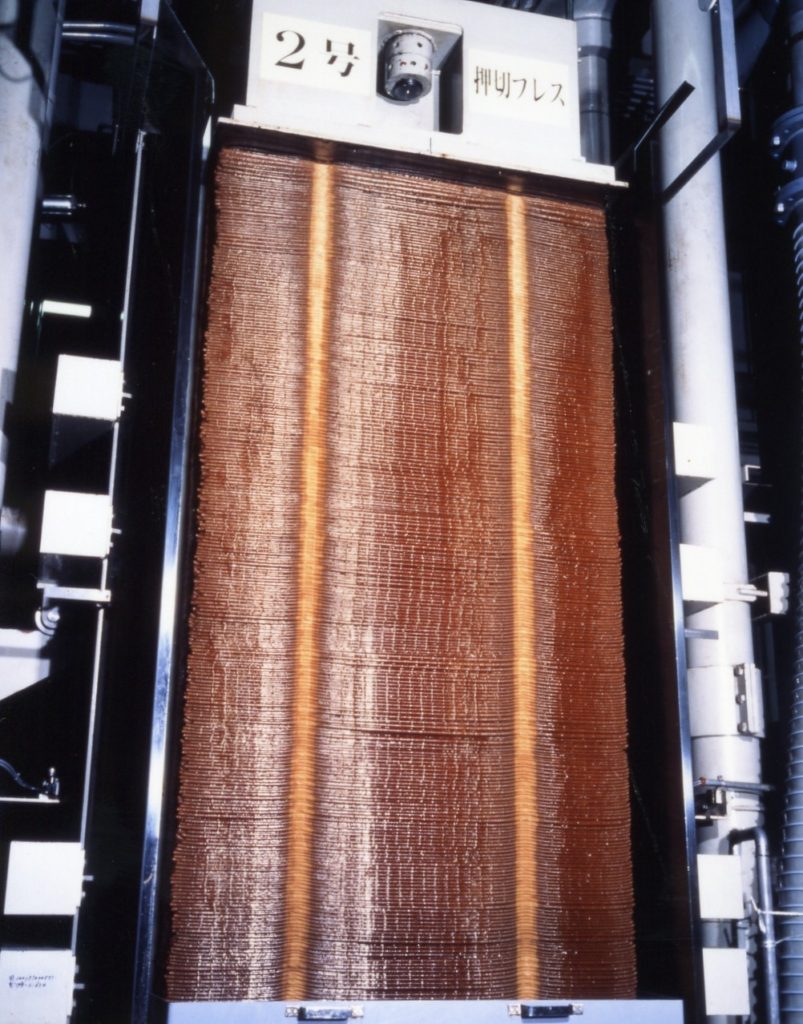

The one room that visitors can have a long look at is the stage of pressing the liquid from the fermented mash. Factory workers oversee the production line where the mash is laid over beige cloth of over 30 meters in length. This mesh material is still the preferred choice to separate the liquid from the solid.

The highlight of the Kikkoman factory has to be a visit to Mame Café, its small cafeteria for visitors. There are free samples of tofu on little platters to be tasted with three types of soy sauce: regular, light-colored, and low-sodium.

Other foods are available for purchase. My recommendation is the soy sauce soft cream is made either with soymilk for a lighter taste or with cream for a richer flavor. The soy sauce gives it a light brown color and a caramel-like accent. There is a hint of saltiness but it complements the sweetness of the ice cream very well.

The small dish of cold noodles is refreshing as is the warm bowl of vegetable stew. The adventurous will have fun roasting their own rice crackers and brushing them over with a thick soy sauce.

The tour ends with each visitor given a bag with information pamphlets and a bottle of the original Kikkoman soy sauce.

Also on the Noda Kikkoman factory premise is the “Goyogura,” (Imperial storage house) the historical brewery that has been making soy sauce for Japan’s Imperial Family since 1908. The building on site was originally constructed in 1939 but at another location in Noda. In 2009, Kikkoman decided to take apart the structure and relocate it using the same material but reinforced and repainted. The Goyokura at Kikkoman is a “working museum.” The soy sauce for the Imperial Household is still produced in the traditional way here and it is a museum exhibiting the historical brewing techniques, tools and equipment used. Visitors can actually see the royal soy sauce fermenting in large cedar vats lacquered in a vibrant red. To control the temperature and humidity for fermentation, there is a mechanism to open and close the roof of the storage space. Only the finest domestic soy beans, wheat and salt are used. Starting in 2012, a limited quantity of Goyokura soy sauce will actually be available for purchase to the public.

Making Soy Sauce:

- The first step is to process the raw materials. Soy beans are soaked in water for an extended time, steamed at a high temperature and then drained. Wheat is roasted and then crushed by rollers the shell sorted out.

- Lactic acid bacteria, enzymes and a type of fungus called aspergillus are added to the mixture. Every manufacturer uses its original fungus to create their special flavor. A specific Kikkoman aspergillus has been used since the company was founded. This mixture is then spread out onto large trays for three days with the temperature and humidity of the room carefully controlled. This produces a fermented liquid called shoyu koji.

- The shoyu koji is then mixed with salt water to become moromi, a mash which is fermented and aged in huge metal tanks for months.

- The final step is pressing the moromi to become finished soy sauce. The mixture is placed on long strips of cheese cloth where gravity makes the liquid drip down. Then the mixture is pressed down by machines for 10 hours to drain all the liquid from the mash.

- This liquid is called raw soy sauce. For several days, inside huge storage tanks, the liquid is naturally separated into sediments at the bottom, oil on top and soy sauce in between. Then the clear soy sauce is heated to be pasteurized and stop fermentation of the enzymes. The taste, color and aroma of the final product are adjusted before bottling.

The Noda Kikkoman Factory Tour

Tours are held six times a day and free.

To make a reservation, call 04-7123-5123

(Reservations should be made in Japanese. Weekends are booked months in advance but there are usually spots available for weekday tours. At the main factory and at Goyogura, there are English-language pamphlets and displays.

Kikkoman Noda Factory

110 Noda, Noda City, Chiba Prefecture

278-0037

http://www.kikkoman.com/soysaucemuseum/index.shtml

(The factory is a 3-min walk from Noda-shi Station on the Tobu Noda Line.)

Blog News about Japan 未分類

Omosubi Kororin

Roly-Poly Rice Balls

Once upon a time, long ago, an old woodcutter sat himself down on an old tree stump at lunchtime.

“The rice balls my wife makes are truly delicious,” he said to himself as he opened the bamboo-bark wrapping.

One of the rice balls tumbled to the ground, rolling over and over and falling into a hole nearby.

“Oh no! What a waste!”

The old man peered into the hole. From the depths he could hear this song:

- Roly-poly rice ball Rolling along

- Tumbling and falling Plop! into the hole.

“How strange,” thought the old man. “Who can be singing?”

He had never heard such beautiful singing before.

“Well then, one more.”

The old man dropped another rice ball into the hole.

As soon as he did so, the song returned.

- Roly-poly rice ball Rolling along

- Tumbling and falling Plop! into the hole.

“This is interesting.”

The old man quite happily put all the rice balls into the hole and didn’t eat even one himself.

The next day, the old man had his wife make even more rice balls than the day before. Then he climbed up to the mountains.

He waited for lunchtime, then – roly-poly, roly-poly – he dropped the rice balls into the hole.

This time he heard the same pretty song he had heard the day before, coming from the hole.

“Oh dear, oh dear! I’ve lost the rice balls. But I want to hear more…I know! I’ll go into the hole and try asking to hear it again.”

Rolling like the roly-poly rice balls, the old man went into the hole.

Down there he found a great number of mice – too many even to count.

“Welcome, old man. Thank you for all the delicious rice balls,” said the mice, lowering their little heads and bowing in gratitude to him.

“And now, to show appreciation, we will make rice cakes for you.”

The mice brought out a mortar and pestle, and singing,

- Whack! The mice are making rice cakes.

- Whack! Whack! Down in the hole.

they began to make rice cakes.

“These rice cakes are delicious. There is nothing better than your rice cakes and your song!”

After the old man had feasted on the rice cakes, he went home, carrying as a souvenir a little magic mallet that, it was said, would give him anything he wanted.

“Oh my wife, what is it that you want?” asked the old man.

“Well, there are many things I’d like to have, but how good it would be to have a lovely baby,” answered the old woman.

“Well then, let’s try it!”

The old man only had to swing the little mallet, and there was a baby on her knee.

Of course, it was a proper human baby.

And the old man and the old woman lived happily ever after, raising the baby together.

おむすびコロリン

むかしむかし、木こりのおじいさんは、お昼になったので、切りかぶに腰をかけてお弁当を食ベる事にしました。

「うちのおばあさんがにぎってくれたおむすびは、まったくおいしいからな」

ひとりごとを言いながら、タケの皮の包みを広げた時です。

コロリンと、おむすびが一つ地面に落ちて、コロコロと、そばの穴ヘ転がり込んでしまいました。

「おやおや、もったいない事をした」

おじいさんが穴をのぞいてみますと、深い穴の中から、こんな歌が聞こえてきました。

♪おむすびコロリン コロコロリン。

♪コロリンころげて 穴の中。

「不思議だなあ。誰が歌っているんだろう?」

こんなきれいな歌声は、今まで聞いた事がありません。

「どれ、もう一つ」

おじいさんは、おむすびをもう一つ、穴の中へ落としてみました。

するとすぐに、歌が返って来ました。

♪おむすびコロリン コロコロリン。

♪コロリンころげて 穴の中。

「これは、おもしろい」

おじいさんはすっかりうれしくなって、自分は一つも食ベずに、おむすびを全部穴へ入れてしまいました。

次の日、おじいさんは昨日よりももっとたくさんのおむすびをつくってもらって、山へ登っていきました。

お昼になるのを待って、コロリン、コロリンと、おむすびを穴へ入れてやりました。

そのたびに穴の中からは、昨日と同じかわいい歌が聞こえました。

「やれやれ、おむすびがおしまいになってしまった。

だけど、もっと聞きたいなあ。

・・・そうだ、穴の中へ入って頼んでみることにしよう」

おじいさんはおむすびの様にコロコロころがりながら、穴の中へ入って行きました。

するとそこには数え切れないほどの、大勢のネズミたちがいたのです。

「ようこそ、おじいさん。おいしいおむすびをたくさん、ごちそうさま」

ネズミたちは小さな頭を下げて、おじいさんにお礼を言いました。

「さあ、今度はわたしたちが、お礼におもちをついてごちそうしますよ」

ネズミたちは、うすときねを持ち出して来て、

♪ペッタン ネズミの おもちつき。

♪ペッタン ペッタン 穴の中。

と、歌いながら、もちつきを始めました。

「これはおいしいおもちだ。歌もおもちも、天下一品(てんかいっぴん)!」

おじいさんはごちそうになったうえに、欲しい物を何でも出してくれるという、打ち出の小づちをおみやげにもらって帰りました。

「おばあさんや、お前、何が欲しい?」

と、おじいさんは聞きました。

「そうですねえ。色々と欲しい物はありますけれど、可愛い赤ちゃんがもらえたら、どんなにいいでしょうねえ」

と、おばあさんは答えました。

「よし、やってみよう」

おじいさんが小づちを一振りしただけで、おばあさんのひざの上には、もう赤ちゃんが乗っていました。

もちろん、ちゃんとした人間の赤ちゃんです。

おじいさんとおばあさんは赤ちゃんを育てながら、仲よく楽しく暮らしました。

Blog News about Japan 未分類

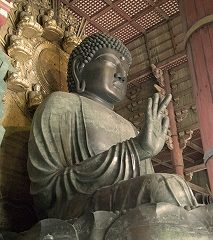

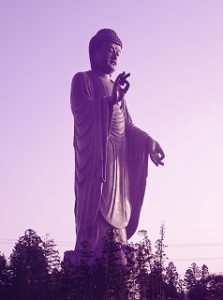

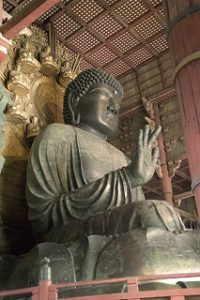

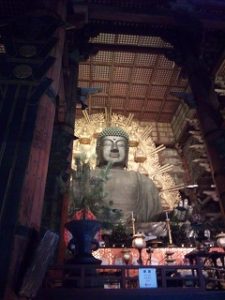

Big Buddha Statues in Japan

The Land of the Great Buddhas

In the eyes of some outsiders, Japanese may seem to take a cavalier attitude toward religion, visiting at Shinto shrines for prayers at the new year, holding weddings at Christian churches and conducting their funeral rites at Buddhist temples. It must be acknowledged that few Japanese possess a strong awareness of religion in their daily lives. Nevertheless, according to statistics, some 96 million Japanese regard themselves as Buddhists. Considering there are somewhat more than 300 million Buddhists in the world, this would make Japan one of the largest Buddhist nations. Japan is home to approximately 75,000 Buddhist temples and monasteries, and more than 300,000 statues and figures of Buddha can be found around the country. Many of these statues play a major role in domestic tourism. Here, we’d like to introduce some of the largest and best known.

(1) Ushiku Daibutsu: Japan’s Largest Buddha

Height: 120 meters

Year erected: 1993

Notable features: The world’s tallest bronze statue of a human figure, as indicated in the Guinness Book of Records. It is also the world’s third highest in terms of its standing height.

Location: Ushiku-Jyoen cemetery (Ushiku City, Ibaraki Prefecture)

URL: http://daibutu.net/ (in Japanese only)

(2) Tajima Daibutsu: Comparatively New Figures in the Remote Mountains

Height: 25.3 meters

Year erected: 1994

Notable features: A total of 20,000 workers in China labored for more than three years to produce the world’s largest wooden figure, one of three at the site. Their entire surfaces are covered with gold leaf. On the south side of the hall, a 70-meter high, five-story pagoda towers looking over them.

Location: Chorakuji temple, Kami-cho, Mikata-gun, Hyogo Prefecture

URL: http://www.tajimadaibutsu.jp/eng/ (in English)

(3) The Takaoka Daibutsu: One of Japan’s Three Most Revered

Height: 15.8 meters

Year erected: 1933

Notable features: Said to be the crowning achievement of Takaoka City’s bronze craftsmen, the Takaoka Daibutsu is said by some to be one of Japan’s three great Buddhas together with those in Nara and Kamakura. However, the Great Buddha in Gifu also lays claim to this distinction.

Location: Daibutsuji temple, Takaoka City, Toyama Prefecture

URL: http://www.info-toyama.com/_sightseeing/000040.html (in Japanese only)

(4) The Daibutsu of Nara: Historic and Famous

Height: 18 meters

Year erected: 752 AD

http://www.todaiji.or.jp/

Notable features: The joint labor of 2.6 million workers, one university professor has calculated that costs to build the Great Buddha and hall, in today’s money, would come to approximately 465.7 billion Japanese yen ($5.8billion). A designated national cultural treasure and the world’s largest wooden structure, the main hall also houses the figure of the two Kongorikishi, Agyo and Ungyo (guardians of the Buddha), and numerous other treasures, making it a famous tourist destination.

Location: Todaiji temple, Nara City, Nara Prefecture

URL: http://www.todaiji.or.jp/ (in Japanese only)

(5) The Daibutsu of Kamakura: A Famous Figure Close to Tokyo

Height: 13.3 meters

Year erected: 13th century (estimated)

http://www.todaiji.or.jp/

Notable features: A designated national cultural treasure and awaiting recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage site, Kamakura’s Daibutsu is regarded as the symbol of Kamakura city, although its builder and year of construction are uncertain. Along with the Great Buddha in Nara, it is considered one of Japan’s most famous. As it is located just one hour by train from Tokyo, it is a popular destination for school outings.

Location: Kotokuin temple, Kamakura City, Kanagawa Prefecture

URL: http://www.kotoku-in.jp/en/top.html/ (in English)

Other Places Worth Visiting

(6) The Daibutsu of Tokyo

Height: 12.5 meters

Year erected: 1977

Notable features: The largest figure of Buddha in Tokyo. Was built as a memorial to victims of the 1945 Tokyo Air Raids and 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake.

Location: Jorenji temple (Itabashi Ward, Tokyo)

(7) The Daibutsu of Hyogo

Height: 18 meters

Year erected: 1991

Notable features: The first great Buddha was erected here in 1891, but it was melted down for its metal content during World War II. This statue, the second incarnation, was built with donations from local supporters, citizens and businesses.

Location: Nofukuji temple (Kobe City, Hyogo Prefecture)

[Sidebar]

Daibutsu is the Japanese term, often used informally, for large statues of Buddha. Buddhism was introduced to Japan by Emperor Shomu, who commissioned the construction of the Daibutsu at the Todaiji temple in Nara in 752 and propagated Buddhism as an instrument for national stability. Since then, large images of Buddha have been erected at numerous locations around Japan. While there is no height which officially qualifies a figure to be designated “daibutsu,” the Japan’s most authoritative dictionary, the Kojien, defines a daibutsu as standing higher than joroku (one mon, six shaku by the old measurement system, or about 4.85 meters).

Blog News about Japan 未分類

Japan’s Flea Market

Let’s Go Browse at an Antique Market!

Japan has many antique markets that operate on the grounds of temples and shrines, usually on special days on the calendar or during festivals. Located apart from stalls selling walk-away snack foods, professional vendors of antiques or individual collectors arrange merchandise for sale. Unlike flea markets in which used clothing or various old objects are sold by amateurs, the antique markets in Japan offer a variety of traditional handicrafts and objets d’art, and can be enjoyed just for the view alone. Here, we’d like to introduce four of Japan’s regularly held markets, two in Tokyo and one each in Kyoto and Osaka.

<Shitenno-ji temple, Osaka>

At this huge temple, the 21st day of each month is observed as “Daishi-e,” the date the Buddhist saint Kobo Daishi (774-835), also known as Kukai, passed away. The 22nd is observed as “Taishi-e,” the date Prince Shotoku (574-622), a political leader and ardent proponent of Buddhism, of passed away. On these two days, some 300 vendors set up shop on the temple grounds. In addition to snack foods and items of daily use, antique items are sold. The five-story pagoda and other buildings on the temple grounds are open to the public for free.

Location of Shitenno-ji temple: five minutes’ walk from Osaka’s JR Shitenno-ji station

Operating dates: 21st & 22nd of each month

Hours: 8:30 ~ 16:00

Number of stalls: approx. 300

URL: http://www.shitennoji.or.jp (in Japanese only)

<Kitano-Tenmangu, Kyoto>

This Shinto shrine, located north of the Kyoto central station, enshrines a prominent scholar and statesman, Sugawara Michizane (845-903). On the 25th day of each month, which coincides with the day Sugawara passed away, many worshippers and tourists visit the shrine. As Kyoto has the highest population of students relative to its overall population, many people come to write prayers on ema (votive tablets), or to pray for success at school entrance examinations. The many goods arranged for sale at these markets are characteristic of Kyoto and are quite appealing.

Location of Kitano-Tenmangu: 15 minutes’ walk from JR Enmachi station

Operating dates: 25th of each month

Hours: 6:00 ~ 16:00

Number of stalls: approx. 300

URL: http://kitanotenmangu.or.jp/english/

<Oedo Antique Market, Tokyo>

This antique market was organized from 2003, to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the designation of Edo (present-day Tokyo) as the capital of Japan’s Tokugawa dynasty. Located conveniently just minutes away from the famous Ginza shopping district, the market also offers western antiques, paintings and many other types of goods. It attracts large numbers of foreign visitors, and many of the vendors are able to communicate in English.

Location of Oedo Antique Market: Outside Tokyo International Forum, close to JR Yurakucho station

Operating dates: 1st and 3rd Sunday of each month (subject to change, please check dates on the Web site)

Hours: 9:00 ~ 16:00

Number of stalls: approx. 250

URL: http://antique-market.jp/eng/

<Tomioka Hachmangu Antique Market, Tokyo>

Here can be found over 140 stalls offering ceramics, Buddhist icons, toys and other items. Some shops sell swords, firearms armor, helmets, etc., which are registered as authentic antiques, and in order to take them out of Japan, application must be submitted to a prefectural board of education and a waiver obtained. As such permits may require one week or longer, tourists on a short visit will probably have to content themselves merely by seeing and touching the goods.

Location of Tomioka Hachmangu Antique Market: a three-minute walk from Monzen Nakacho subway station (Tozai Line).

Operating dates: 1st and 2nd Sunday of each month

Hours: 6:00 ~ 17:00

Number of stalls: approx. 140

URL: http://www.tomiokahachimangu.or.jp/ (in Japanese only)

Blog News about Japan 未分類

Brian Williams: The Nature of Art, the Art of Nature

Brian Williams: The Nature of Art, the Art of Nature

By Eric Johnston

Many foreign artists call Japan home, and the ancient capital of Kyoto and the surrounding area in particular have long attracted a wide variety of visual and performing artists from both Japan and abroad. But few have enjoyed such successful and distinguished career as Shiga Prefecture-based Brian Williams.

The 61 year Williams, born of American missionary parents, was raised in Peru and Chile. After finishing high school in California, where he’d initially thought about becoming a scientist, he decided on a career in art. In 1972, not long after graduating college, he arrived in Japan with a backpack and 300 dollars in his pocket.

He’s been here ever since, painting watercolors, which he fell in love with when he was 16. Currently one of the very few full time foreign artists in Japan, Williams recently scored an unprecedented success with a special showing this past May of his parabolic paintings at Kyoto’s famed Kiyomizu-dera, the first any foreign artist has ever been granted the honor of exhibiting at the world famous World Heritage Site.

For Williams, the Kiyomizu-dera exhibition was the highlight of a four-decade artistic career that combines his love of traditional Western watercolors with Japanese traditional art and aesthetic forms.

“I came to Japan because I wanted to study Japanese landscape paintings and woodblock prints, as there is a strong relation to watercolors. I was especially interested in the technique, and the tools used for Japanese landscapes and woodblocks. The idea was to use Japanese technology as a base for creating something original,’’ Williams says.

Western brushes, for example, are often designed so that the hairs on the sides are short while the hairs in the center are long. But Williams says he was fascinated by a Japanese brush called a mensofude, which has short hairs in the center and long hairs on both ends, as well as the hirafude brush.

As for his paintings, Williams says that they combine the concept of painting atmosphere, which comes from the Japanese tradition to painting, and the concept of painting light, which comes from the Western tradition.

“The idea of painting the atmosphere around an object, not just the object, is an idea I got from Japan,’’ he says.

As a landscape painter, Williams is particularly interested in two concepts very much at the heart of traditional, rural Japan. The first is genfukei, or, to roughly translate, the primal landscape. Writing in Kyoto Journal No. 68 (published in December 2007), Williams noted that the word carries a connotation of natural beauty, especially among older Japanese who grew up in traditional houses in the countryside. Many of his paintings capture the beauty of genfukei. Not only in his home of Shiga Prefecture but all over Japan, and the world. Williams has painted landscapes in Europe, the UK, the U.S., South America, Tibet, China, and Mongolia, among others.

The other concept Williams is passionate about is satoyama. This ancient Japanese farming tradition, which emphasizes sustainable use of limited farm land and efficient use of natural resources, was last year recognized by the United Nations Convention of Biodiversity as an important and effective way to halt worldwide biodiversity loss. For Williams, it’s not just about preserving the aesthetic beauty of Japan’s countryside for his paintings, but also encouraging environmental stewardship.

“From the standpoint of biodiversity, it’s precisely the cultivated lands (the foundations of satoyama) that we ignore at our peril. The Satoyama Initiative shows that a rich variety of specimens can coexist and even prosper with judicious human use of the land,’’ Williams wrote in a special report on biodiversity and satoyama that was published by Kyoto Journal last year.

He emphases that rural and agricultural lands, thought of by many urban dwellers as simply empty spaces, must also function as habitats for all life forms, and that, in order to effectively combat biodiversity loss, urban areas need to incorporate traditional principles of satoyama as much as they can.

“More than half of the world’s population is living in urban areas, and this figure is expected to rise to 80 percent by 2030. Satoyama was born out of traditional and even reverent connection with nature, and emphasis living on land in a sustainable manner,’’ he says.

While traditional watercolor prints remain Williams’ first love, in recent years he has spent more and more time on his newest passion: parabolic paintings. Unlike traditional paintings on a flat surface, inside a square or rectangle-shaped frame, parabolic paintings are created on curved surfaces that come in irregular, non-linear shapes. Williams got the idea for doing parabolic paintings after he visited the Dordogne in France and Altamira in Spain to view the Paleolithic art on the curved surfaces of the caves.

He returned to Japan and began working on his own parabolic paintings, and, through his contacts, was eventually invited to exhibit them at Kiyomizu-dera last May. While the event drew far more people than originally predicted, Williams admits that they don’t receive praise from everybody.

“The reaction is usually divided. Some people say ‘Wow,’ the first time they see the paintings. But others say ‘This looks like a craft, not an art,’’’, he says.

Williams says there are a number of keys to his success in Japan over the past 40 years, besides a natural artistic talent, and they are critical for any foreign resident who decides to live and work in Japan.

“In order to succeed in Japan, you need to work hard, pay attention to quality and detail, and you must be dependable. You also need a good social sense, a feeling for how Japanese see and do things, which may be often more valid than the way you always did something. You have to ‘go native’, to a certain extent, and yet you have to keep your sense of foreign uniqueness,’’ he says.

“In short, you need to understand the importance of the Japanese phrase isshokenmei. You have to compete with yourself first and foremost, no matter what you do or what your profession is. You can’t be satisfied with doing the same way, all of the time.’’

For on Brian Williams, please visit his website www.brianwilliamsart.com

Blog News about Japan 未分類

Issun-bōshi (The One-inch Boy)

A long, long time ago in a certain village, there lived an old man and his wife. They had no children so they prayed to God, “God, please give us a baby. Even if it were a tiny, tiny, thumb-size baby, we would be happy and grateful.”

Their prayers were answered and they were really blessed with a tiny, tiny baby. The baby was a boy about the size of the old man’s thumb. In delight, they named him Issun-boshi (One-Inch Boy).

One day, when he had grown older, Issun-boshi said to his parents, “I would like to go to the capital and work there. Please make arrangements for my journey.”

The old man therefore made a sword out of a needle that fit Issun-boshi perfectly. His wife made a boat out of a wooden bowl so that Issun-boshi could journey down the river to the capital.

“Here, take this needle sword.”

“Here, use this chopstick as an oar.”

“Thank you, Father and Mother. Goodbye, now.”

Issun-boshi thus set out for the capital, rowing his bowl boat skillfully. When he arrived at the capital, Issun-boshi visited the most magnificent house in the town.

“Hello, is anyone around?”

“Yes, I’m coming —. Oh?”

The servant who had come out wondered.

“No one’s up here. I thought someone had called out.”

“Hey, look down! I’m down here!”

The servant finally found the tiny figure of Issun-boshi who was standing at the foot of geta or Japanese sandals arranged on the floor of the entrance.

“Oh my goodness, what a tiny boy he is!”

Issun-boshi was then hired as a bodyguard for the princess of the house.

One day, Issun-boshi was attending the princess who made a visit to a temple. On their way home from the temple, all of a sudden, two giant demons appeared.

“Wow, look at this beautiful girl. Let’s take her with us.”

One of the demons tried to catch the princess.

“Wait!”

Issun-boshi drew his needle sword and sprang upon the demon. However, the demon said, “Ha-ha, are you a bug or what? Get lost!”

The demon picked up Issun-boshi with its fingers and swallowed him whole. It was completely dark inside the demon’s stomach. Issun-boshi swung his needle sword around and stabbed everywhere inside the stomach. The demon cried out in pain,

“Ouch! It hurts!”

The demon immediately vomited up Issun-boshi. The other demon said, “All right. Now I’ll squash the bug boy!” But Issun-boshi held up his needle sword and jumped into the demon’s eye this time. The demon was frightened.

“Eek! Help, help!”

The two demons ran away crying loudly.

“Huh! Learn your lesson and never come back! — Oh? What is this, Princess?”

There was something strange left on the ground after the demons had gone.

“Oh dear, this is what’s called Uchide-no-kozuchi, the mallet of luck. If you shake it, you can have anything you want.”

So Issun-boshi asked the princess, “Please shake the mallet wishing that I can grow taller.”

The princess happily shook the mallet saying, “Issun-boshi, grow taller.”

Every time the princess shook the mallet, Issun-boshi grew taller and taller and finally became a tall and handsome young man.

Issun-boshi then married the princess, and worked hard and did well. It is said that he rose up to a very high position.

Blog News about Japan 未分類

Saitama’s Ramen Academy

Ramen is a Japanese dish composed of Chinese-style noodles in a rich broth, topped with various condiments. Originally based on a similar Chinese dish introduced in the Taisho Era (1912-1926), it spread rapidly around Japan, and began to take on a distinctive Japanese style. Today in terms of popularity ramen could be said to rank as one of Japan’s “national dishes,” and has also been popularized in other Asian countries and in the West. Ramen “food parks” have sprung up around Japan. The dish shown in the photo was taken at the “Ramen Academy” in Saitama City. The “academy,” as it’s called, features five shops serving famous ramen styles from around the country. After a shop “graduates” from the academy, the space is opened to the next entrepreneur. As the competition is intense, the less successful shops may shut down earlier than planned, to make way for another vendor.

Blog News about Japan 未分類

A Whopper of a Blue Whale Biggest one in Japan

The largest creature that currently exists on our planet is the Blue Whale, specimens of which have been found that measured 34 meters in length. This model went on display outside the National Museum of Science in Tokyo’s Ueno Park, to the delight of visitors who have enjoyed posing for photos in front of it. This model is the third of its kind, having been preceded by two other species, a Fin Whale and Humpback Whale. Before these, the skeleton of an actual whale was once displayed there.