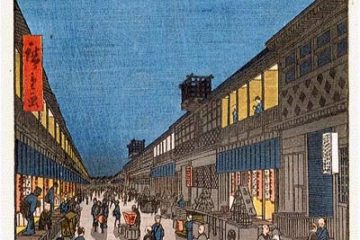

Ukiyo-e is a kind of woodcut print which flourished from about the 1680s and 1850s in Japan. The word ukiyo-e means “pictures of floating world” as the themes usually depicted the beautiful, fleeting world of entertainers such as kabuki actors and geisha. Later, pictures of scenery would also become popular. Because the printmaking medium allowed for mass reproduction, ukiyo-e became a form of artwork that the rising merchant class could afford. Overseas, this stylized pop art garnered the attention of Impressionists such as Monet. Vincent van Gogh created his interpretations of two famous works by ukiyo-e master Utagawa Hiroshige. Because they often depicted urban life in the Edo period, ukiyo-e also became culturally important as historical testimonies.

An Amateur’s Initiation into Ukiyo-e Printmaking

If you are an admirer of ukiyo-e woodblock prints, you can attend a half-day workshop to make your own. Boso-no-Mura is a museum in Chiba Prefecture where visitors can learn about Japanese culture firsthand by making various traditional foods, arts and crafts themselves. If you are lucky, the receptionist might tell you there is a cancellation for the ukiyo-e printmaking workshop. An extremely popular course, it usually gets booked up months in advance.

The smell of fresh ink is slightly overwhelming when you first enter the printmaking workshop. Assistants ensure beginners master the basic concepts by experimenting on scrap paper. At this stage, it seemed fun and easy.

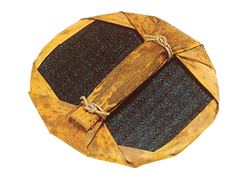

Ukiyo-e is made by a method where multiple blocks are used for separate portions of the image. On one block, only images designated a certain color would be carved onto the wood. The painting we would work on that day was a scene of the Sumida River and consists of seven color blocks. We are each given a piece of Japanese “washi” paper, which absorbs the ink beautifully, with the drawing etched in black lines. The most difficult and important aspect of suri printing is lining up the paper precisely so the color inks are pressed onto the designated places of the drawing. A specialized tool called the baren, a small, wooden iron, is used to burnish the colors onto the paper. Gradation is a high level skill that is created by applying various levels of pressure with the baren. The order of the plates used progresses from the lightest color to the darkest and from the areas with the least color to the most. The real ukiyo-e process is daunting.

A significant appeal of the workshop is spending time with Keizaburo Matsuzaki. Born in 1937, he has been making prints for almost 60 years. Between 1998 and 2004, Matsuzaki undertook a tremendous project in completing the 120-print collection of Utagawa Hiroshige’s “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo” for the Tokyo Edo Museum. In 2001, he received the distinction of being a Designated Traditional Artisan by the city of Tokyo. He is also recognized as a cultural treasure of Arakawa city, Tokyo and generally recognized as a living master of suri, Japanese woodblock printing.

It is a treat to watch Matsuzaki inspect each block diligently, chiseling away at edges that have softened with use. Even for a class of amateurs, for every new block used, he would make multiple trial copies until the amount of ink is optimal. To be an eye-witness to the passion, the commitment and the painstaking attention to detail of a master artisan is truly inspiring.

The term eddoko (Edo’s Child) is often bantered around to describe someone who is opinionated, stubborn and straight-talking. Because Japanese society is cloaked in vague polities, edokkos are frequently admired for their outspoken attitude. Matsuzaki is a true edokko.

“Bad, bad! That’s really horrid.” Matsuzaki does not mince words. “Did you not listen to a word I said? Watch now and this time, don’t forget. Remember to line up the corner, don’t rush and keep the paper straight,” he addressed me specifically as I carelessly rushed through the yellow woodblock. The color did not match the lines of the paper and I shuddered at the realization that in this craft, this is no second chance.

With some trepidation, I lined up the orange woodblock and pressed my paper with the baren. I unpeeled it to see that the orange colors fit within the lines perfectly. Matsuzaki inspected. “Ah, spectacular. I knew you weren’t stupid!” he said.

I felt accomplished and almost moved to tears. A woman doing her fifth workshop with Matsuzaki, smiled kindly at me, “Way to go,” she whispered. A completely unexpected development of attending this print workshop is the comradely formed between the seven participants. Mutual encouragement is needed to console each other through this artisan initiation and survive Matsuzaki’s barbed remarks.

The worse fear of ukiyo-e printmaking is getting the wrong color on an absolutely irrelevant place. When I confessed to the class, a man reassured me that since we were doing scenery, even the worst mistake would not be as bad as when he did a print of a geisha – and clearly misplaced the lips. “With two sets of lips, she looked like an alien,” he says. Yet this man persists on coming. “I’m still not good but I am getting better and there’s satisfaction in that,” he says. Indeed, the appeal of being an artisan is that it requires diligence and perseverance – egalitarian qualities that are not dependent on natural born talent.

By the end of the afternoon, Matsuzaki’s insults have turned to praises as everyone in the class manages to produce gradual shades of red and blue. In talking rough, he treats a group of amateurs like real apprentices and pushes all of us to concentrate and produce our best. He says our minor mistakes are what make woodblock prints unique because each one is different. For 400 yen, you bring home your original ukiyo-e print. But the experience of learning from a true master of Japanese craftsmanship is – priceless.